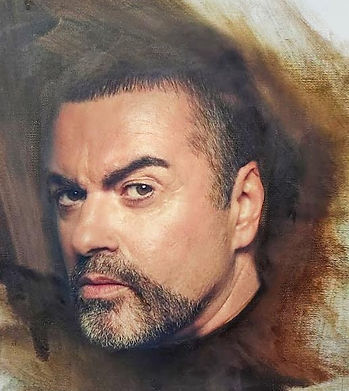

Nigel Whittaker Art

The man who turned pop into confession and confession into craft.

George Michael died on Christmas Day, 2016, and there was something almost intolerably symbolic about the timing. Christmas is meant to be a season of light of family, warmth, belonging yet here was a death that felt less like celebrity news and more like personal weather. For those of us who grew up with his voice in the walls of our lives, his passing didn’t arrive as gossip. It arrived as loss. The world seemed briefly harsher, as though one of its softer intelligences had been removed.

What are we celebrating when we celebrate George Michael? In a straightforward way, we are celebrating one of the great pop voices: warm as velvet, capable of steel, expressive without needing excess. But that’s too blunt. There have been many good voices hundreds of technically gifted singers who could hit a note and hold it there. What made George Michael rare wasn’t simply his instrument; it was the mind and feeling behind it. His artistry had control. His voice didn’t merely carry a melody. It carried a personality measured, sensual, wounded, searching.

He could be glamorous without being glossy. He could make desire sound intelligent, heartbreak sound precise. Where other pop stars worked in drama, he worked in depth. Even when the song was bright, even when the beat was built for movement, there was an undertow: a shadow of seriousness, the faint sense that he understood the cost of wanting things too much.

It’s easy now to talk about the Wham! years as pure sunshine the neon innocence of a decade that still believed tomorrow might be brighter than today. But even there, the talent is visible if you bother to look. He wasn’t simply a frontman. He was writing his way towards something. There’s craft in the choruses, intelligence in the construction. The lightness isn’t stupidity it’s performance.

And performance, for George Michael, became a kind of camouflage.

When Faith arrives, it doesn’t feel like a career step. It feels like a declaration. This is what we sometimes forget about him: how ferociously competent he was. Pop history likes its icons chaotic. It loves collapse and carnage. But his genius was not disorder it was precision. He could write. He could arrange. He could produce. He could shape a song so that it doesn’t merely “work”, but strikes, commands, lingers.

And yet even at his most swaggering, there’s tension in the music. The confidence is real but it’s also defensive. The seduction is real but it’s also a mask. It’s the sound of someone giving the world what it demands while keeping something back. The songs are mass-market, but the feeling in them is private secrets whispered into a megaphone.

Then come the deeper works: the songs where he stops acting and begins confessing, or where the acting itself becomes confession.

Take Praying for Time. It isn’t merely a political song. It’s existential. He looks at the appetite of the world greed, cruelty, hypocrisy and sings with the terrible clarity of someone who can’t unsee what he has seen. It doesn’t feel like pop moralising; it feels like someone trying to remain decent while the age itself conspires against decency.

And then there is love the central subject of popular music, and yet so rarely treated with emotional intelligence. Most love songs are conquest or complaint. George Michael’s best work treated love as something harder: a moral event. A test of bravery. A site of self-deception.

In Father Figure tenderness becomes seduction, seduction becomes power, power becomes need. The song is intimate and unsettling at once — not the fantasy of romance, but the psychology of it. In One More Try, he makes fear inseparable from desire. It is a song made of hesitation, of exhaustion, of someone asking not for pleasure but for safety. And he sings it with such restraint that the emotion becomes more credible. He doesn’t oversell the wound; he holds it.

The later years carry their own weight. There is weariness, scandal, tabloid hunger, public unkindness. It’s tempting to call it decline. But perhaps it’s more accurate to call it the cost of being sensitive inside a machine that punishes sensitivity. The cost of being human while famous. The cost of needing love when millions believe they already own you.

And yet the voice remained. More than remained it deepened. He gained that late-stage quality possessed by the very best singers: less perfection, more truth. The voice became heavier, lived-in, seasoned. The elegance stayed, but innocence fell away. He sounded like someone who had learned the hard fact that success doesn’t heal you; it only enlarges the space in which you must confront yourself.

When he died, alone, it felt cruelly fitting. A man who gave shelter to so many through music could not always shelter himself. That is not rare among artists. It may be the private tragedy that underwrites much of the art we most treasure.

So what are we celebrating?

Celebrating an artist who made pop sophisticated without making it cold. A craftsman of feeling. A man who could write a hook big enough for the radio and then smuggle in a line that lands like personal revelation. We are celebrating his refusal to become a simple story in a culture that prefers simple stories. His insistence on dignity. His capacity for generosity not only in private acts, but in the giving of his voice, his craft, his humanity.

And perhaps most of all, we are celebrating this: the way his music continues to do what the greatest music does. It makes you feel less alone not by distracting you, but by telling the truth about the most private parts of being alive.